SUSTAINABLE FOREST MANAGEMENT

Improvement Cuts

The thinning of a forest stand requires the removal of suppressed and diseased trees to provide growing space for better quality trees.

Harvest Cuts

Harvest cuts require the removal of mature trees to promote the establishment of a new generation of trees and increase the diversity within a forested area.

Wildlife Habitat Improvement

Wildlife habitat improvement cuts help enhance an area to meet the biological needs of a wildlife species, such as food, cover and breeding grounds.

FOREST MANAGEMENT

In remote sections of GMF, protected by swamps and rough terrain, there are a few remnant trees that are over 350 years old. These were left untouched during the charcoaling and tanbark era, which ended around the turn of the 20th century, leaving very few other trees in the area.

Wildlife management and research have also been conducted throughout the history of the forest, as part of our forest stewardship. Under careful protection, wildlife has returned in increasing numbers. Wild turkey, white-tailed deer, coyote, black bear, and moose have all re-established resident populations.These are the focus of a number of studies by state and university researchers.

In addition to the terrestrial ecosystems, there are seven ponds on the property and numerous areas of wetland and riparian habitat. These, along with some 40 acres of beaver flow, afford excellent habitat for waterfowl.

In general, Great Mountain Forest covers a broad upland of heaving glaciated crystalline rock. Elevations range from 1,200 feet to nearly 1,800 feet, except at the southwestern extremity where the upland drops sharply to the ancient limestone formations of the Housatonic Valley. There the elevation is just under 700 feet. Soils and climate never favored agriculture here, but they are good for tree growth. Precipitation, with an average annual rainfall of 52 inches, well distributed throughout the year, and an average annual snowfall of 96 inches, favors the forest. So too does the fact that snow cover usually remains well into April, which helps to reduce spring fire hazards.

The elimination of fir is perhaps the most important since ecological change during the past 100 years, as slash fires were a regular and sometimes very destructive part of charcoal making. With the wildfires suppressed, as well as care forest stewardship practices, the forest has been able to regenerate and has again become a health ecosystem. The forest now is mainly composed of transition hardwoods, with a strong representation, over much of the area, of northern hardwoods mixed with hemlock and white pine. Native stands of red spruce and red pine can also be found. At the lower elevations of the Housatonic Valley, some typical Appalachian hardwoods appear, such as tulip poplar, black and chestnut oaks, various hickories, dogwoods, and sassafras.

In addition to a wide variety of forest types, a wide range of animals and plants populate the first including some rare ones. Endangered species observed in the forest include timber rattlesnakes and bald eagles, in addition to several invertebrates and woodland amphibians, which are rare or threatened in the state. Over 21 species of rare or endangered plants have been located and documented throughout the forest.

All of these factors are taken into consideration when planning GMF’s sustainable forest management practices.

Photos courtesy of GMF archives

Photos courtesy of GMF archives

Sustainable Forest Products

Witch Hazel

South of the Yale Camp, flanking the Chattleton Road, grows one of GMF’s more storied forest products—witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana). One can identify the witch hazel shrub by its grey meandering branches and the surprising autumn bloom of its yellow tendrilled flowers—think of forsythia on a bad hair day. These flowers and the shrub’s seed pods appear after the leaves have fallen, making witch hazel all the more mysterious and dramatic.

Witch hazel is known for its medicinal qualities that Native peoples harnessed for their own use. These included easing sore muscles, treating wounds, and brewing a medicinal tea. The shrub contains flavonoids and tannins that are astringent and help stop bleeding.

Its name has less to do with black magic than its branches’ flexibility. The word “witch” derives its meaning from Middle English for wych or wyche, meaning pliant or flexible. It is thought that Mohegans showed English settlers how to use its Y-shaped branches for “dowsing,” which is the ability to find water underground, also called water witching.

Since 2002, GMF has harvested its annually certified organic witch hazel. GMF contracts with second-generation witch hazel harvester Eugene Buyak to chop the shrub the old-fashioned way—with an ax.

Rotating around the prolific witch hazel stands, which need a minimum of 10 years to regrow, Buyak harvests over a hundred tons of witch hazel each season. He chips the branches and stems in a specialized chipper and sells them to American Distilling, owner of Dickinson Brands.

T.N. Dickinson’s and Dickinson’s Original labels have been familiar sights in medicine cabinets since the late 1800s. They produce most of the distilled witch hazel in the U.S.

GMF’s witch hazel reaches consumers worldwide and is also a key ingredient in countless other cosmetics, skincare products, and over-the-counter medications.

Photos courtesy of GMF archives

Maple Syrup

For 70 years, Great Mountain Forest has been producing maple syrup. The GMF sap house located near the Forestry Offices in Norfolk, CT produces 75 to 100 gallons of syrup per season from approximately 450 taps. A small number of buckets are still used, but now the majority of the sap is collected from gravity tube-line technology.

Information collected during the sugaring season includes the amount of sap that was collected, its sugar content and the amount of syrup produced. Anecdotal observations such as the first robin or blue bird sighted or what particular species of trees are starting to bud are also noted. Select individual sugar maple trees along the collection route were routinely checked for the sugar content in their sap and the amount of sap collected per tap was measured as the 6-week season progressed.

All these records in conjunction with the daily weather readings from Norfolk 2SW, the National Weather Service weather station operated by GreatMountain Forest, provide interesting observations for present day environmental concerns.

Deer Management

Great Mountain Forest supports a healthy deer population with a deer-herd management program that has been conducted as a forest-management practice for the past 50 years. Maintaining a proper deer density on the landscape promotes both a healthy deer herd and a sound forest ecosystem. The overpopulation of the species results in overbrowsing, which stalls forest regeneration.

GMF participants in this program serve two roles: to harvest deer during Connecticut’s annual hunting season and to monitor the forest and wildlife.

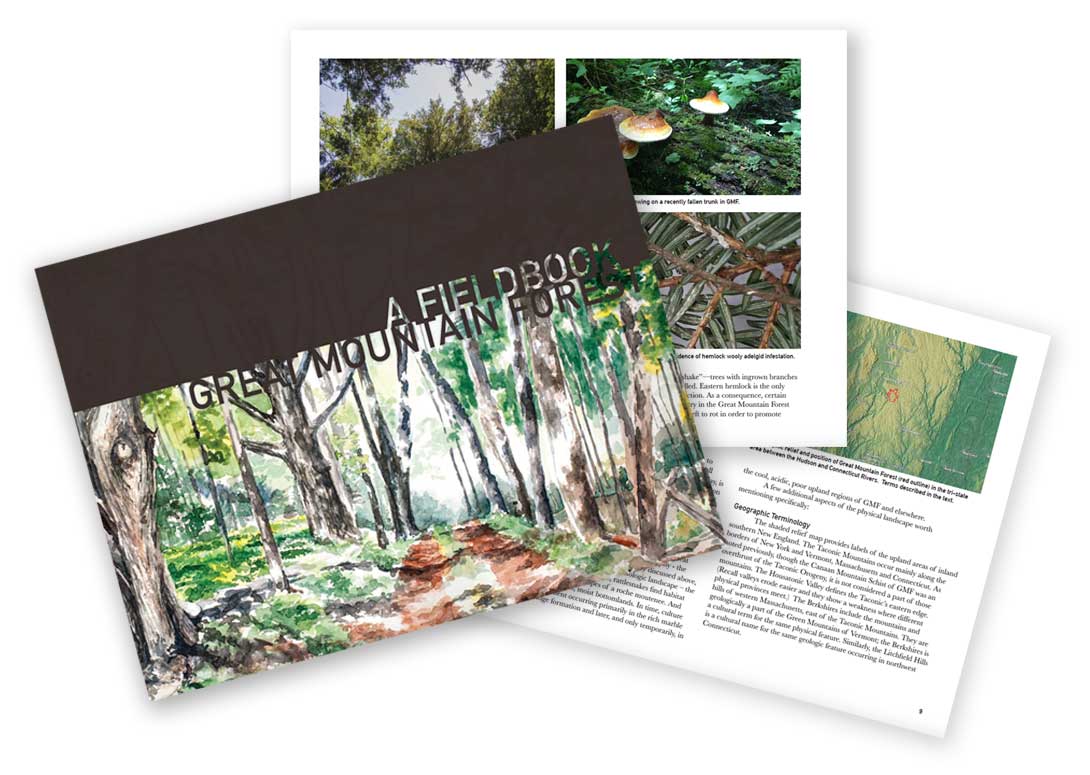

A Fieldbook: Great Mountain Forest

The Global Institute of Sustainable Forestry

This field resource book makes it easy to explore

and learn about Great Mountain Forest. It shows you how to read the landscape by introducing you to places and features that tell the stories of the Great Mountain Forest. By using it you will observe, learn, and study the ecology and history of the Great Mountain

Forest.

Forest Research

Great Mountain Forest has a long history of supporting forest research. Many research institutions and their affiliates utilize GMF because of its locale, long-term ownership, diverse ecosystems and continuous weather collection data for the past 90 years.

Here is a list of past and current research on Forest Management.