PREVIOUS WEATHER REPORTS

Restoring a Changing World: Forest Management for Invasive Species, Carbon, and Biodiversity with Dr. Sara Kuebbing

A GMF Winter Lecture

Eastern deciduous temperate forests are facing growing global change disturbances such as accumulating invasive species, temperature warming, and extreme weather events. Major international policy initiatives, like the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), stress the importance of sustainably managing forest ecosystems to preserve resilience to these global change pressures. Join Dr. Sara Kuebbing as she highlights the global changes linked to nonnative, invasive plant growth in forests, the response of forest plants to warming spring temperatures, and how we can use forecasting models to inform management efforts!

Dr. Sara Kuebbing

Research Scientist at the Yale School of the Environment and Director of Research of the Yale Applied Science Synthesis Program

Dr. Kuebbing is trained as an ecologist with expertise in conservation biology, invasion biology, plant ecology, community ecology, and ecosystem ecology. Her research focuses on how humans can make informed decisions on how to best protect and conserve landscapes, ecosystems, and all the species that lives within them. She works with a variety of scientists, land managers, and policymakers to focus research questions and share results. She is excited to be the inaugural director of YASSP, which is a research program space for open collaboration among practitioners, academics, and policymakers to develop applied science that guides sustainable land management.

Prior to moving to YSE, Dr. Kuebbing was an Assistant Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Pittsburgh. Her research training includes postdoctoral positions with the Yale Institute for Biospheric Studies and the Smith Conservation Fellows Program, a PhD from the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Tennessee and a BS from the Department of Entomology & Wildlife Conservation at the University of Delaware.

DATE: Saturday, February 28, 2026

TIME: 4:00 PM – 6:00 pm

LOCATION: The Norfolk Library

9 Greenwoods Road East

Norfolk, CT

Promoting Forest Health in the Aftermath of Invasive Pests & Pathogens with Dr. Elisabeth Ward

A GMF Winter Lecture

Connecticut’s forests are changing in response to novel pests, pathogens, diseases, and other stressors. Join Dr. Elisabeth Ward as she explores the impact pests, pathogens, and diseases have on our local forests. Focusing on emerald ash borer and beech leaf disease, Dr. Ward will discuss potential management practices that can fend off these disturbances and safeguard the health and resiliency of our forests. Learn more about how you can take an active role in protecting our woodlands!

Dr. Elisabeth Ward

Scientist at Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station

Dr. Elisabeth Ward is a Scientist at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station that leads a research program focused on improving forest ecosystem health and resiliency. She received her BS in Biology from Brown University and her MS and PhD from The Forest School at the Yale School of the Environment. Her current research examines how changing conditions in Connecticut, such as tree mortality from invasive pests and pathogens, are shifting the structure and composition of forests as well as the ecosystem services they provide.

DATE: Saturday, February 7, 2026

TIME: 4:00 PM – 5:30 pm

LOCATION: The Norfolk Library

9 Greenwoods Road East

Norfolk, CT

Seeing the Forest for the Bees with Biologist Kass Urban-Mead

Pollinator Conservation Biologist & NRCS Partner Biologist

The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation

As a pollinator conservation specialist at Xerces, Kass Urban-Mead works with staff and research partners to develop technical guidelines and provide training on pollinator conservation practices. She directly assists with planning, designing, installing, and managing habitat in forested, agricultural, and urban areas. She completed an MSc at the Yale School of Forestry. Her PhD work in the Cornell Entomology Department characterized the wild bee communities active in early spring forests and forest canopies. She quantified the canopy pollen consumed by spring-active bees, and the movement of bees between forests and spillover into apple orchards. Kass grew up raising 4-H dairy goats in the lower Hudson Valley of NYS.

DATE: Saturday, January 17, 2026

TIME: 12:00 PM- 1:30 PM

LOCATION: The Norfolk Library

9 Greenwoods Road East

Norfolk, CT

GMF Mindful Forest Immersion Series

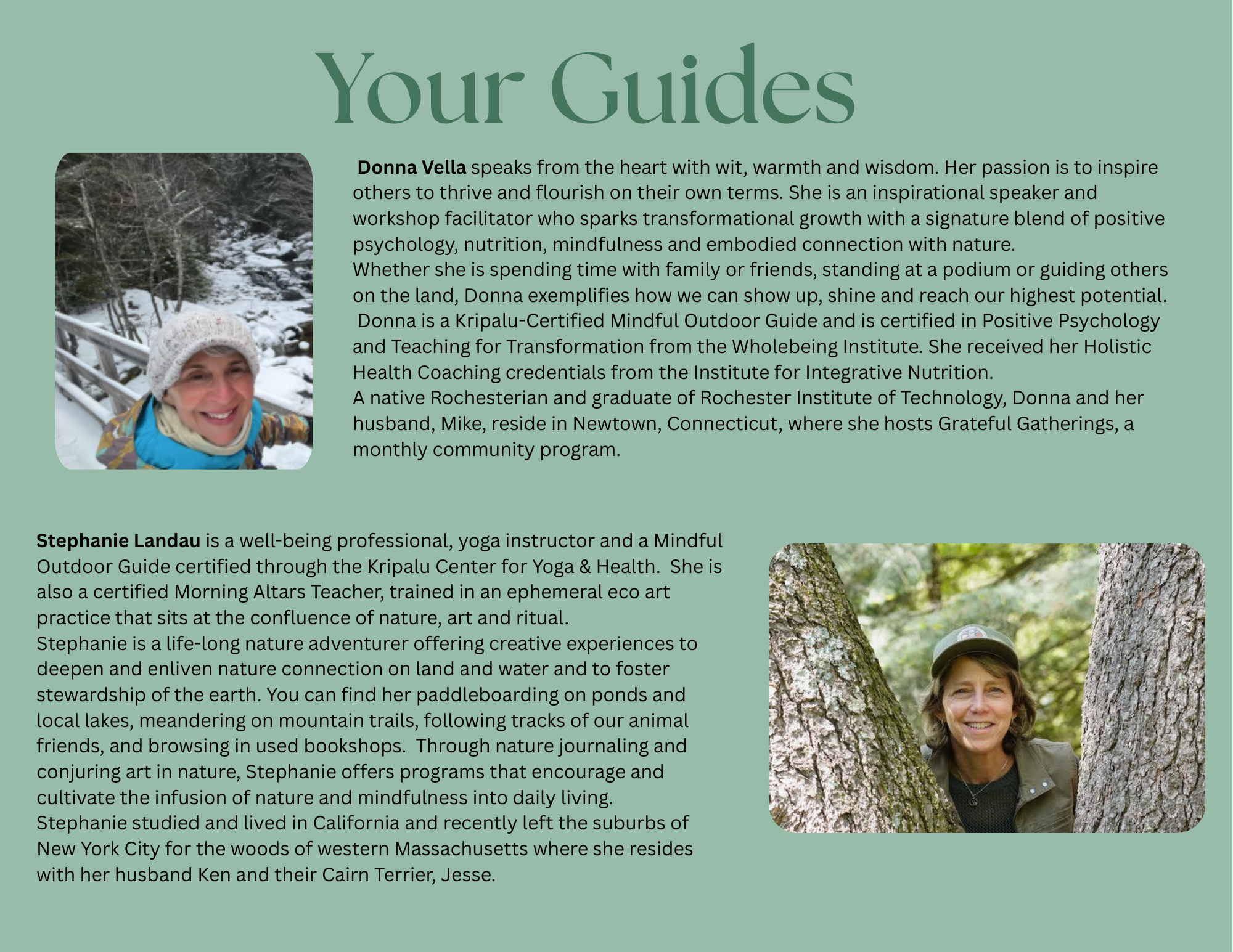

Step into the stillness and beauty of Great Mountain Forest with our three-part Mindful Forest Immersion Series. Guided by certified Kripalu Mindful Outdoor Leaders, each seasonal gathering invites you to slow down, breathe deeply, and connect with the forest—and yourself—through practices of mindfulness, creativity, and community.

Celebrate the turning of the seasons with contemplative outdoor experiences designed for all levels. Each session includes a gentle guided walk, sensory awareness practices, seasonal tea and snacks shared in circle, and a unique creative or reflective activity inspired by the rhythms of nature.

- 🍂 Fall Forest Immersion: Nature’s Ephemeral Art

Saturday, November 1, 2025 · 10:00am – 12:00pm - Location: 177 Canaan Mountain Road, Falls Village, CT

- Create a collaborative forest mandala while exploring themes of impermanence and beauty.

- ❄️ New Year Forest Immersion: The Art of Wintering

Sunday, January 4, 2025 · 12:00pm – 2:00pm - Location: 90 Golf Drive, Norfolk, CT

- Honor the wisdom of winter with a fire-gazing meditation and reflection on resilience and renewal.

- 🌱 Spring Equinox Forest Immersion: Emerging Light

Saturday, March 21, 2026 · 1:00pm – 3:00pm - Location: East Gate, 201 Windrow Road, Norfolk, CT

- Awaken your senses and welcome in Spring through guided mindful walking, simple movement, nature meditation, and community conversation and listening.

- This Spring Equinox offering includes an introduction to nature journaling and sketching — not as an art class, but as an awareness-building practice of wonder, curiosity, and creativity.

No art, hiking or meditation experience is needed.

Open to participants ages 14 and up. Tickets: $25 per person.

Join us in honoring the forest as teacher and companion—an invitation to pause, notice, and grow alongside the changing seasons.

Winter Lecture Series -The Engaging Landscape

Saturday February 1, 2025

4:00 PM – 5:30 PM

Lecture Location:

The Norfolk Library

9 Greenwoods Road East

Norfolk, CT 06058

Winter Lecture Series: Tom Blagden is an accomplished nature photographer and writer with over 40 years of experience. Tom’s photographs have graced the covers of renowned magazines, including Smithsonian, Audubon, Nature Conservancy, and Sierra.

“My goal in sharing these photographs of GMF is to immerse viewers in as full a sense of place as possible and as seen through fresh eyes. Nature photography has the power to instill an emotional connection to our landscape that then allows us to assign a higher sense of value.”

Winter Lecture Series -Mycorrhizal Network

4:00 PM – 5:30 PM

Lecture Location:

The Norfolk Library

9 Greenwoods Road East

Norfolk, CT 06058

John Wheeler is a mycologist and founding member and president of the Berkshire Mycological Society. For 34 years John has hunted and identified wild mushrooms in Massachusetts. Former Prof. at Simon’s Rock college of Bard. John has encounter over 1,000 different species of mushrooms in the Berkshires alone.

John will talk about the underground network of fungus and the connections that benefit trees in the forest. Participants will also learn about how mushrooms can be used to booster health.

Frozen in Time

Frozen in Time: A Glacial Legacy at GMF

Long before 1909, when Frederic C. Walcott and Starling W. Childs acquired the 400 acres of barren land around Tobey Pond, which would become Great Mountain Forest, other forces were at work that would shape the land in ways far more dramatic than any human intervention. Some 15,500 years ago, advancing and melting glaciers created land formations—including kettles, erratics, roche moutonnées, and glacial polish—which are visible in the forest today.

Tobey Pond, The Finest of Kettles?

Tobey Pond is an example of a kettle, formed when vast chunks of ice were buried under sediment. The melting ice left a depression in the earth, and because the water table was high enough, a pond was formed. Nearby, where the water level was marginal, a kettle bog was born. With its black spruce (likely the southernmost stand in New England), Tobey Bog is proof of this glacial activity. Where the water table is low, a land depression formed on the forest floor, as seen in the white-pine-filled depressions of the old Norfolk Downs golf course, now part of GMF.

Erratics

A hike through GMF invariably brings you to a glacial erratic. These sizable boulders are solitary reminders of the force of glacial ice, moving boulders far from home and depositing them in a new locale, often great distances away. One storied example of a GMF erratic is Meetinghouse Rock off Meekertown Road. This rock became the civic centerpiece for the town meetings held by the residents of Meekertown in the late 1700s. Here, at the house-shaped boulder, residents debated and decided on issues of their common interest. Another glacial erratic that visitors can see up close is located on Crossover Trail.

Roche Moutonnée

Despite the French moniker, roche moutonnées (sheep rock) are common in the Northeast. In GMF, several sites fall into this glacial category, most notably Wapato Lookout and a lookout off of a Crossover Trail spur.

Roche moutonnées formed in GMF when thick glacial ice from the north moved over hilly or mountainous landscapes. Rocks and debris trapped in the glacier scour the north-facing side of the rock. Often, striations in the rock provide evidence of the glacier’s path.

As the glacier descends on the other side of the peak, the force and friction of the ice begin to “pluck” rock fragments and chip away at the surface. This chipping away at the rock’s surface creates a rocky cliff or depression where water can accumulate to form a tarn or small lake. Both Wapato Pond and Crissey Pond are tarns resulting from glacial activity. Over time, Wapato Pond evolved into a wetland. However, in the 1930s, the creation of a dam allowed the pond to reassert itself to what we see today.

Glacial Polish

Glacial polish, evident on the balds of both Matterhorn and Stoneman Summit, results from a glacier scouring the bedrock clean, leaving striations in the rock behind. These striations point to the path and trajectory of the glacier. Matterhorn Summit is accessible via trail spur off Sam Yankee Trail. The Iron Trail reaches Stoneman Summit.

More information about GMF’s glacial and geologic history can be found in our May 2023 newsletter article Deep Time Under GMF and in A Fieldbook: Great Mountain Forest. Download the GMF Points of Interest Map and related descriptions from our website to explore GMF’s geologic and glacial history from its trails.

Guided Winter Walk with Mike Zarfos

Guided Winter Walk

with

Mike Zarfos

Time to sign up: Holiday Wreath Workshop

Holiday Wreath WorkshopSaturday, December 7th: morning session 9 AM -12 PM or afternoon session 1 PM – 4 PM and… Saturday, December 14th: morning session 9 AM -12 PM or afternoon session 1 PM – 4 PM |

| Join GMF and friends by the wood stove to put your creative foot forward and make a holiday wreath that speaks to you. There will be hot cider warmed on the stove, snacks, and great conversations. Bring your favorite pruning shears and creative mind!

200 Canaan Mountain Road, Falls Village, CT |

GET IN TOUCH!

860 824-8188